Feb 25, 2020

As Nurses Prep for Coronavirus, Lessons from the Ebola Outbreak

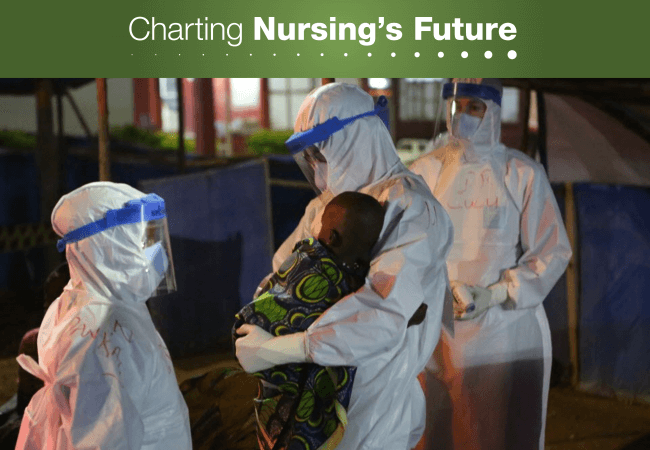

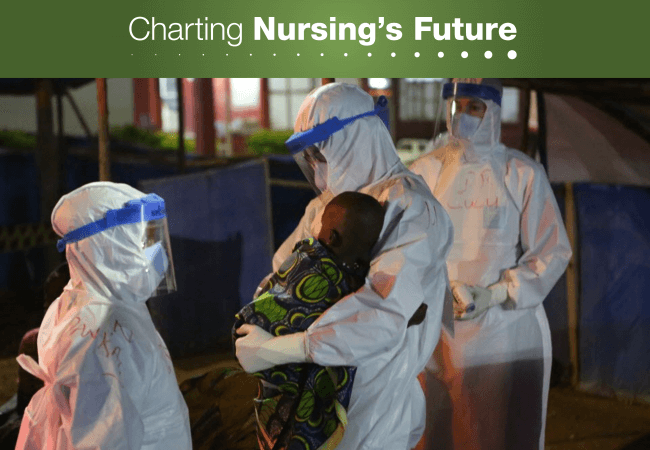

A nurse with Boston-based Partners in Health swaddles a child at an Ebola treatment center in Sierra Leone. Health workers treating patients with the new coronavirus must also wear protective clothing and take other precautions to avoid contracting or transmitting the virus. Photo credit: Rebecca E. Rollins, Partners in Health.

In 2016, Charting Nursing’s Future released a policy brief on disaster preparedness and response. Among other topics, the brief looked at how nurses responded to the Ebola virus outbreak and the impact of that outbreak on how nurses did their work. Now that U.S. clinicians have begun encountering patients with the novel coronavirus that originated in Wuhan, China, COVID-19, we are sharing lightly edited excerpts from our earlier article. We hope these observations from nurses who confronted the Ebola outbreak will help inform their peers who are preparing for patients with coronavirus.

The 2014–15 Ebola outbreak proved to be a cautionary tale for our nation’s response to new infectious diseases. Nurses were squarely in the public eye: examined, criticized, and, at times, praised as singular heroes amidst failing institutions. The nation learned that some hospitals and regions are better prepared than others to address infectious disease epidemics; that nurses are on the front lines of care; and that, without adequate training and protection, nurses put their own health and safety in jeopardy to care for the public.

Teamwork and Preparation Save Lives

When the head nurse of the Nebraska Biocontainment Unit (NBU) donned protective equipment to meet her first patient with Ebola, she had practiced the ritual for nine years. She and fellow nurses even picked the equipment and designed the protocol.

After the NBU agreed to accept the first patient, staff repeated drills and refined protocols so that patients would receive optimal care while staff stayed safe.

But preparation was just one factor that helped Nebraska Medicine and Emory University Hospital safely and effectively treat patients with Ebola. NBU’s clinical care was shaped by a deliberate culture of collaboration. Team members shared information at shift-change huddles. Nurses, doctors, and respiratory therapists spoke up if they saw something troubling and avoided traditional hierarchies that hamper open communication.

It’s no coincidence that the NBU was designed and staffed during Nebraska Medicine’s journey to Magnet® designation. To earn Magnet status, hospitals must demonstrate that staff work as a team, and that the institution fosters a culture that lets nurses flourish professionally; grants professional autonomy and decision-making authority at the bedside; and gives nurses a voice in their work environment.

“It’s about the involvement and engagement of staff at the front line,” said Shelly Schwedhelm, MSN, RN, NEA-BC, executive director, emergency preparedness and infection prevention at Nebraska Medicine. “Including them in decisions about policies and protocols as well as in critical thinking to solve problems and confront unique situations—this was a daily requirement during care of patients with Ebola.”

At Emory University Hospital, staff on the isolation unit team that cared for Ebola patients called themselves a “family,” underscoring the collaborative nature of their work. All team members, regardless of role or profession, were empowered to share accountability for following safe practices. Nurses and physicians implemented an active buddy system for donning and doffing protective gear.

“The first thing hospitals have to do is work on the culture,” said Susan Grant, MS, RN, FAAN, who was then chief nursing executive at Emory Healthcare (the comprehensive network that includes the hospital). “Every member of the team has an equal role. It’s about partnership and interprofessional collaboration. In order to be patient- and family-centered, you have to be team-centered.”

Behind the Headlines

At Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas, poor communication among a nurse, a physician, and a patient led to the discharge of Thomas Duncan, the first patient diagnosed with Ebola on U.S. soil.

When Duncan was later readmitted and presumed infected with Ebola, nurses followed the CDC’s guidance on protective gear, but the agency’s directives shifted on numerous occasions. This undermined nurses’ confidence, according to an independent panel report released by the facility. Ultimately, two Texas Health nurses were infected with the virus; they recovered, but Duncan died.

The hospital is a two-time Magnet-designated institution, underscoring the challenges faced by any non-biocontainment hospital in treating an emerging infectious disease. Unlike nationally designated treatment centers, Texas Health had no warning that an Ebola patient would walk through its doors.

“There are aspects of what happened at Dallas that could have happened anywhere,” said Nebraska Medicine’s Schwedhelm.

Not everyone agreed. Nina Pham, RN, who contracted Ebola while taking care of Duncan, is suing Texas Health Resources, saying it did not adequately train and protect nurses. Since the incident, the hospital announced that it has improved its workflow and medical record software to clearly highlight travel risk and emerging infectious diseases; put in place new procedures to more quickly identify at-risk patients; developed a triage procedure for at-risk patients that quickly isolates them; and increased its emphasis on communication between nurses and physicians.

Preparing for the Unknown

For decades our nation has felt isolated from infectious diseases that prevail in other parts of the world, but the arrival of Zika on the heels of the Ebola crisis brought home our vulnerability, and the advent of coronavirus adds to it.

“We’re used to having a vaccine or a cure,” said Pamela A. Thompson, MS, RN, FAAN, chief executive officer of the then-named American Organization of Nurse Executives. “Ebola forced us to ask: How do we create a system that allows us to manage the ambiguity of what we are preparing for, while keeping our patients, and the entire health care team, safe?”

As a first step, she recommended nurses and other health care personnel maintain their skill in standard (once called “universal”) precautions—protocols for handling blood and bodily fluids as if they were infectious.

Effective communication is also critical. To forestall public alarm, Thompson said messages to staff, patients, and the community must be clear and fact-based.

Organizational best practices may include:

- screening patients at all entry points, including primary care venues;

- communicating travel histories to all team members;

- establishing systems of community-wide coordination;

- forging ties with public health agencies to increase awareness of potential threats.

Even with these practices in place, Thompson concluded, “There’s always going to be this unknown piece—something you didn’t anticipate—and all the systems you designed to that point may not work. That’s where providers’ creativity and ingenuity come in.”

A longer version of this article first appeared in When Disaster Strikes: Nurse Leadership, Nursing Care, and Teamwork Save Lives. You can access the full brief on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation website.