Introduction

The National Academy of Medicine on May 11, 2021 released its much-anticipated report, The Future of Nursing 2020-2030: Charting a Path to Achieve Health Equity. Like its predecessor from 2010, this report will influence the direction of nursing and health care for years to come.

The report hones in on the problem of health disparities, rooted in centuries of injustice that will take substantive societal change to solve. Achieving health equity will require serious reflection on our identities and responsibilities as nurses, nurse champions and contributing members of society. Then we will need the willpower to turn that reflection into action.

Getting started

What do we mean by health equity?

The report considers how nurses should best address social determinants of health and provide “effective, efficient, equitable, and accessible care for all across the care continuum.” To prepare to meet that goal, we’re reviewing what key terms like “social determinants” and “health equity” actually mean.

The Campaign for Action gathered several authoritative definitions for the Health Equity Toolkit. Authored by members of the Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Steering Committee, the toolkit guides readers through key terms using resources from the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

This graphic from RWJF illustrates the difference between equality and equity.

Visualizing Health Equity: One Size Does Not Fit All Infographic by RWJF on RWJF.org

As several of the resources cited in the toolkit make clear, health equity is about more than ensuring that everyone has access to the same resources. It’s about addressing the disparities that can prevent people from living full and healthy lives.

Here are more articles we’re reading to understand key concepts in health equity:

- “Meeting Individual Social Needs Falls Short of Addressing Social Determinants of Health” – Health Affairs

- The HealthyPeople.gov website from the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion includes modules to aid in mastery of concepts like social determinants of health

Addressing the crisis at hand

What does the COVID-19 pandemic teach us about health equity?

If the nation did not know what health equity meant before 2020, it certainly ought to know now.

As the COVID-19 pandemic upended life in the United States, it did not impact all populations equally. Native American, Black, and Latino people were significantly more likely to die from the virus; when the data is adjusted for age differences between populations, it reveals that these groups were 2.7 times more likely to die than White Americans in 2020. Much more information on the pandemic’s unequal toll is available from APM Research Lab’s “Color of Coronavirus” project.

Source: APM Research Lab, Color of Coronavirus • Pacific Islander data prior to 10/13 did not include Hawaii, as it was not releasing data; its inclusion resulted in an overall drop in the Pacific Islander rate, which begins a new series at 10/13.

We are reckoning with this data through the release of the new NAM report, which also addresses the pandemic and its aftermath. The statement of task called on the committee to consider “The role of nurses in response to emergencies that arise due to natural and man-made disasters and the impact on health equity.” Additionally, the NAM added time to the report development process specifically to address the pandemic and its aftermath.

In the meantime, nurses and others have not been silent about the failures in the response to the pandemic or about the injustices it has revealed. Across the spectrum of care, nurses have seen the impact of the disease firsthand as they have filled every conceivable role, from contact tracing to helping dying patients say goodbye to loved ones.

The unequal impact of the pandemic was also felt by nurses themselves. The Guardian and Kaiser Health News have been tracking health care worker deaths in the United States since the pandemic began. Of the more than 3,600 health care workers who died, 32 percent were nurses. As with the general population, health care worker deaths were disproportionately among people of color. Groups that were particularly hard hit included nursing home staff and nurses born outside the United States, especially nurses from the Philippines.

We will be attempting to understand the pandemic and what it revealed about health disparities for years; it will also be essential to understanding the NAM report and any recommendations to improve health equity. Here are a few more resources for understanding this watershed moment from nurses’ point of view:

- “The time for outrage is now” – Susan Hassmiller, PhD, RN, FAAN, director of the Campaign for Action and a senior scholar in residence at NAM, penned this piece as the scale of the pandemic became clear. “We must commit as a society to address at the roots the social and economic factors that affect health, such as access to high-quality jobs, education, housing, and clean air and water,” she wrote. “We must enact policies that dismantle structural and systemic racism.”

- “The floor is on fire” – Cardiology nurse Jackie O’Halloran sounded the alarm about the challenges clinicians were facing in an op-ed for STAT. In this interview with SHIFT Nursing, she reflects on her decisions to speak up and what nurses’ experiences in the pandemic have to teach us about the future.

Taking on injustice

What systems must we challenge to achieve health equity?

The past year not only brought a global pandemic, but a movement for social justice unlike anything seen since the Civil Rights Movement. The murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement have pushed all sorts of people to think more critically about race, power, and privilege. This includes nurses and other health care providers.

The NAM statement of task calls for “identifying system facilitators and barriers” to health equity. Over the past year, many people have been doing just this kind of work, coming to understand that social ills like racism are not just hateful individual attitudes, but systems of oppression.

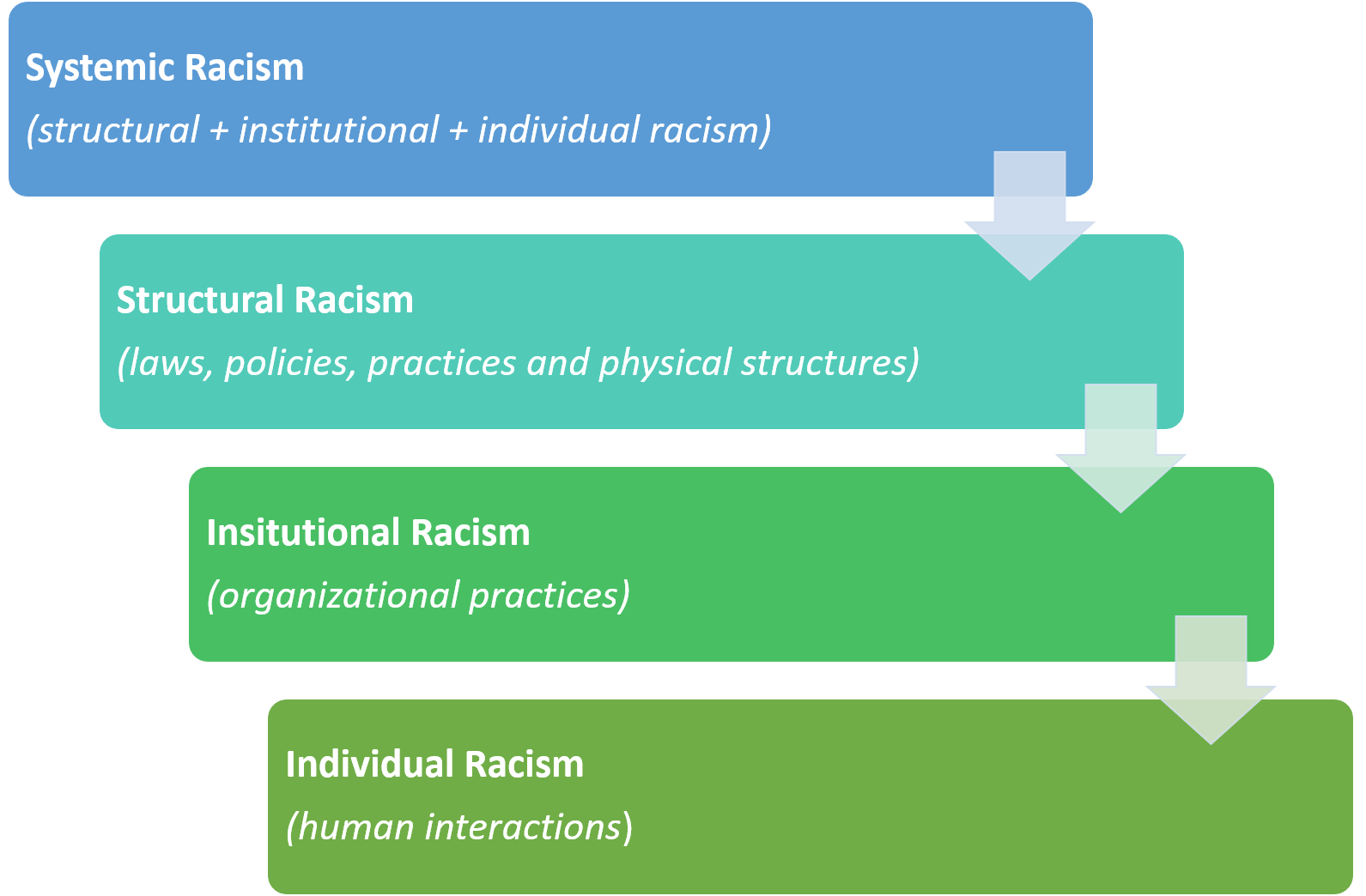

This illustration by Kupiri Ackerman-Barger (PhD, RN), a professor at the UC Davis Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing, explains how racism shows up in systems and structures. As a consultant for the Campaign and the Campaign for Action’s Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Steering Committee, Ackerman-Barger has helped Campaign leaders understand these and other systems that limit people’s ability to lead their healthiest lives.

Many more resources are available to those who wish to understand racism as a systemic barrier to health equity. Some are gaining new perspective from books like How to be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi and Caste by Isabel Wilkerson. We are also learning from authorities on the health impact of racism, such as David R. Williams; here is his TED talk on the subject, which has been viewed more than a million times.

We can also look to positions taken by health institutions. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently declared racism to be a major public health threat, then launched a new resource page to take on the problem. A coalition of major nursing organizations recently launched a National Commission to Address Racism in Nursing.

Of course, racism is one of many elements of systemic oppression that must be understood in order to address health equity. Systems may unfairly limit health equity due to a person’s gender, religion, language, immigration status, sexual orientation, rurality, disability, and other factors. Scholars are also paying more attention to the ways in which these factors intersect. Here are other resources we turn to in order to better understand the systems that impair health and how they might be made more just:

- The Campaign for Action’s Health Equity Toolkit includes a framework to perform a thorough assessment of community health needs.

- The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s County Health Rankings and Roadmaps not only help health care providers understand the state of health in their communities, but also provides insight into the systems that may be holding it back.

- The CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index combines an array of metrics to provide insight into the risks faced by various groups.

Rolling up our sleeves

How do we become change agents for health equity?

The mandate to create health equity in the United States is clearer than ever. But what specifically should the profession of nursing do to rise to the challenge? How should we “serve as change agents in creating systems that bridge the delivery of health care and social needs care in the community,” as the NAM statement of task envisions?

One resource that is helping us think about this question is “Activating Nursing to Address Unmet Needs in the 21st Century,” a report by Patricia Pittmann, PhD, Professor of Health Policy and Management at the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University. Pittmann’s paper was commissioned by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to address key issues of nurses’ capacity to act as change agents ahead of the NAM report.

Pittman addresses a question many nurses have in mind as they approach issues of health equity: haven’t we been here before? As the paper makes clear, pioneering nurses like Florence Nightingale and Lillian Wald meant for the nursing profession to address a broad spectrum of health issues. Nurses in the early 20th century partially achieved that goal through alliances with other professions like social work.

But over time, the role of the nurse came to be viewed in a more narrow, passive, and clinical way. Pittman examines how this happened, as well as today’s opportunities for nurses to lead on health equity issues. There are many reasons to be optimistic, she argues, including new funding models focused on achieving results at the population level, new roles for nurses that draw upon their specific strengths, and the public’s high regard for the nursing profession.

Here are more resources to review as considering how the nursing profession might change to achieve health equity:

- ”Perfectly positioned” – Reviewing Pittman’s study and other recent research, Campaign director Susan Hassmiller makes the case for nurses as health equity leaders in Health Affairs

- ”See What Nurses See” – Patricia A. Polansky, RN, MS, the Campaign’s director of program development and implementation, argues that a broader role for nurses can grow out of their well-established role in patient assessment. This blog post draws on the research of the Campaign’s Population Health in Nursing project.

- ”It’s Not Just Unfair, It’s Inequitable” – Focused on frontline nurses, the SHIFT Nursing website and podcast frequently addresses issues of health equity. Here’s their guide to help their readers get to work on the issue.

Practicing what we preach

How do we diversify the nursing workforce to achieve health equity?

One of the new NAM report’s key purposes is “achieving a workforce that is diverse, including gender, race, and ethnicity, across all levels of nursing education,” according to the statement of task.

While diversity in nursing has improved in some ways, (more detailed data here in the Campaign’s dashboard) we also still have a long way to go. Here’s what we have learned by discussing the issue in the Campaign for Action’s Health Equity Action Forums.

As these virtual gatherings demonstrated, diversity in nursing is about more than just hitting demographic targets. Nurses from an array of backgrounds and other stakeholders, including business, consumer and health care organizations, joined us to highlight the various challenges of building a nursing workforce that genuinely reflects the population it serves — and the new opportunities available if we do.

Just as our understanding of health equity issues is constantly evolving, our efforts to build an inclusive nursing workforce must also expand. Here are other resources we are revisiting before the release of the report:

- The National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses provides some of the most recent data on the nursing workforce

- This article from Nursing Education Perspectives examines how the Collective Impact Model for creating social change could be used to achieve a more inclusive approach in the nursing workforce

- Growing Diverse Nurse Leaders: Current Progress of the Future of Nursing: Campaign for Action (behind paywall)

- The Campaign’s mentor training program, which seeks to improve retention and graduation rates of minority nursing students, and increase the graduates’ passage rates of the National Council Licensure Examination (NCLEX)

Taking action where we are

How do we get to work for health equity in the clinic and the community?

The increasing concern for health equity has included a new view of where health happens. Even though the American health care system is anchored in hospitals, the health of people in America is influenced by all of the places where they work, live, and play.

That’s why one of the issues taken up in the NAM report will be how nurses can address health equity in new settings. Per the statement of task, this will include “the training and competency-development needed to prepare nurses, including advanced practice nurses, to work outside of acute care settings and to lead efforts to build a culture of health and health equity…”

A team from the Campaign for Action began considering these issues several years ago as part of the Population Health in Nursing project. Interviewing leaders in education, public health, community organizing, and more, the team articulated an agenda to develop new population health roles for nurses. They considered how these roles might emanate from heath systems and nursing schools, but also new partners like the housing and education systems.

The Campaign’s Health Equity Toolkit also highlighted several resources nurses can use to initiate efforts on health equity wherever they are. These include:

- This 2016 article in Health Affairs assessing the effectiveness of an array of interventions designed to address social determinants of health.

- The CDC’s Community Health Assessment and Group Evaluation (CHANGE) Tool, which anyone can use to design initiatives that fit the health needs of their communities.

News:

-

What We Learn from Successful School Mental Health Programs

As the calendar flips to August, America’s schools are preparing for a new academic year, the more

Issues: Improving Health Equity,

-

A Delaware School District Program Provides Early Exposure to Nursing

As its 2021 Nursing Innovations Fund project, Delaware’s Brandywine School District (BSD) piloted more

Issues: Improving Health Equity, Increasing Diversity in Nursing, Locations: Delaware,

-

The Role of School Health in Addressing Health Inequities

As the calendar flips to August, America’s schools are preparing for a new academic year, the more

Issues: Improving Health Equity,

-

Nursing Innovations Funds Stimulate a Network of Partnerships for Health Equity

When nurses are empowered to create health equity in their communities, they bring together a more

Issues: Improving Health Equity, Locations: Georgia, Indiana, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Nebraska, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming,