Dec 14, 2017

Law Would Enhance Patient Access to Addiction Treatment by APRNs

No one becomes a midwife to treat drug addiction, but pregnant women and their babies are not immune from the opioid crisis, which claims more than 100 American lives each day. Infants who are exposed to opioids in utero undergo withdrawal after birth and require extra medical care and monitoring, and that can “disturb a lot of normal newborn progression and family bonding,” says Lisa Scott, RN, MSN, NNP-BC, a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Future of Nursing Scholar.

One option—for moms, babies, and communities—is medication-assisted treatment (MAT) for opioid dependency, beginning during pregnancy. MAT, or the use of medications in conjunction with counseling and behavioral therapy to treat substance use disorders, can help people end opioid dependence. MAT is safe for use during pregnancy.

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Future of Nursing Scholar Lisa Scott, RN, MSN, NNP-BC, is studying the consequences of prenatal exposure to opioids.

“It’s much better for the baby to be exposed to an opioid substitute in a treatment program than it is to be exposed to opioids taken illegally,” says Scott, a neonatal nurse practitioner (NP) who has been involved in efforts to help pregnant women who use opioids. “And medication-assisted treatment programs have much higher success rates than abstinence programs.”

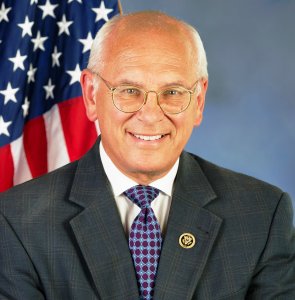

Recently proposed federal legislation would allow certified nurse midwives (CNMs) and other advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) to prescribe MAT. The Addiction Treatment Access Improvement Act of 2017, introduced by US Rep. Paul Tonko, (D-N.Y.) and co-sponsored by six Republicans and four Democrats, would allow CNMs, clinical nurse specialists, and certified registered nurse anesthetists as well as NPs and physician assistants (PAs) to prescribe MAT after they undergo training.

“I heard from an individual last year who had to wait the better part of a year to get service for opioid use,” Tonko says. “When you’re having that moment of clarity, those services need to be there. You shouldn’t have to, in the midst of your struggle, keep searching for a provider who can give you the help that you require.”

Buprenorphine and naltrexone (sold under trade names such as Suboxone and Vivitrol) are both FDA-approved to treat opioid addiction and work by blocking opioid receptors in the brain. Unlike methadone, which must be administered under tightly controlled circumstances at specialized clinics, both medications can be prescribed in primary care settings.

Yet, at present, the number of providers qualified to prescribe MAT is not enough to satisfy the great need created by the opioid crisis. “There’s still a pretty significant gap, both on a state-to-state and a national basis, between the treatment need and the capacity to offer treatment,” Scott says.

Rep. Paul Tonko (D-N.Y.) has sponsored legislation that would make all APRNs eligible to undergo training to provide medication-assisted treatment for opioid addiction.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine supports the Addiction Treatment Access Improvement Act of 2017. The legislation builds on the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000, which allowed primary care physicians to offer MAT, and the Comprehensive Addiction Recovery Act of 2016, which made NPs and PAs eligible to apply for waivers to prescribe buprenorphine. “I think adding more advanced practice nursing professionals to the list of service providers goes a long way in responding to the needs of those who are struggling with substance use disorder,” Rep. Tonko says.

If his legislation passes, pregnant women and other patients who could benefit from MAT may have an easier time finding providers willing to treat their addiction—unless they live in states that place restrictions on APRN practice. APRNs in those states will only be able to prescribe MAT if they have a collaborative agreement with a physician who supports their decision to offer the treatment. In rural and underserved parts of the country, just finding a willing physician collaborator can be difficult, and in some cases, impossible.

The upshot: Patient access to MAT could remain limited, particularly in hard-hit rural areas, even if the Addiction Treatment Access Improvement Act of 2017 becomes law. And when it comes to opioid use, access to treatment may be the difference between life and death.

“What underscores these conversations is the urgency,” Tonko says. “Any hesitation here, any delay, translates into lives lost. The consequences of our inaction would mean that some lives that could be saved are not going to be saved.”