Jun 15, 2020

Nurse Educators Consider the Path Forward During COVID-19

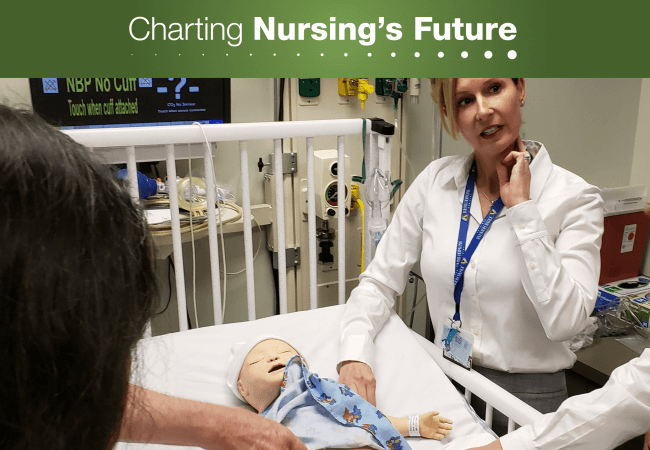

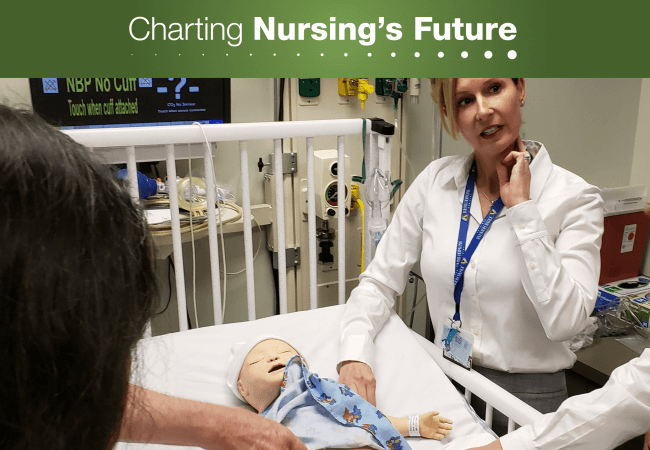

Kristen Brown, DNP, MS, RN, advanced practice simulation coordinator in a sim lab at Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing. The COVID-19 pandemic has spurred nurse educators to reconsider simulation’s role in preparing nursing students for practice. Credit: Nicole Fauteux

When COVID-19 led hospitals and other clinical sites to close their doors to nursing and medical students earlier this year, concerns focused on the coming surge of patients. Would hospitals be overwhelmed? And would graduations be delayed, depriving clinical sites of talent they might desperately need?

The answer to this second question appears to be no, at least as far as entry-level nursing students are concerned. Most of this year’s seniors graduated on time, and, in some cases, early. Many states issued temporary nursing licenses so new graduates could serve on the front lines before sitting for their licensure exams. And with the suspension of most elective procedures, many experienced nurses found themselves furloughed despite the anticipated nursing shortage during the surge.

With these immediate concerns in the rearview mirror, state nursing boards, accreditors, and educational associations are reflecting on the changes schools made to propel their students over the finish line to graduation. Like others teaching throughout the country, nurse educators moved their didactic courses online, but providing clinical experiences during an infectious disease pandemic required additional consideration.

In March, national nursing education associations and the National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) proposed the use of practice/academic partnerships to provide opportunities for students to augment staffing at clinical sites during the pandemic. The model generated enthusiasm in many quarters, but few clinical sites were in a position to establish the partnerships while tackling preparations for a surge in COVID-19 patients. Instead, most programs turned to simulation to replace cancelled clinical experiences.

The Pre-Pandemic Status Quo

Simulation was well established in health professions education prior to the current public health crisis. Educators see it as a way to enhance student learning and provide experiences such as assisting at the birth of a child—an event that can’t be timed around student schedules. Although state rules vary, nearly half of states allowed one hour of clinical simulation to substitute for one hour of in-person clinical experience up to 50 percent of the clinical hours in a given course prior to the pandemic.

The 1-to-1 ratio and choice of 50 percent are not arbitrary. In 2015, NCSBN completed a multiyear study of clinical simulation in entry-level nursing programs, which showed this ratio to be effective in producing clinically competent graduates.

Changes During the Pandemic

Since the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, NCSBN has been monitoring how state nursing boards have changed their requirements to help programs keep their students on track. With the need to find alternatives to working directly with patients, many states that previously limited simulation in nursing courses to less than 50 percent raised their limits; some states already at 50 percent issued temporary rules allowing simulation to substitute for 100 percent of students’ remaining clinical requirements.

“COVID made it a necessity to replace some clinical experiences with simulation, and our programs have done an amazing job,” says Gerianne Babbo, EdD, MN, RN, director of education at Washington State’s board of nursing, the Nursing Care Quality Assurance Commission. In March, the commission provided additional flexibility for nursing programs by allowing simulation to count for 50 percent of total student clinical hours during the crisis. The commission also supported computer-based virtual experiences to count as simulation.

Mary Sue Gorski, PhD, RN

Babbo’s colleague Mary Sue Gorski, PhD, RN, director of advanced practice, research and policy, says few programs were positioned to take full advantage of the 50 percent threshold. “Our annual survey of prelicensure nursing programs showed 5 percent to 10 percent of clinical hours on average were met with simulation, and only one program reached 20 percent prior to the pandemic.” Nevertheless, she expects these changes to provide a springboard for programs that had laid the groundwork for greater simulation use.

In contrast, programs that prepare advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) have not been given the option of substituting simulation for clinical hours. “The APRN certifying bodies have been very clear that they will not change their required number of supervised direct clinical-care hours,” says Michelle Buck, MSN, APRN, CNS, who serves as APRN senior policy advisor at NCSBN. “Clinical hours may be augmented but not replaced with simulation.”

Michelle Buck, MSN, APRN, CNS

That decision does not appear to have prevented most nurse practitioner (NP) students from graduating on time. “We did an informal survey of what boards were hearing from APRN programs, and a surprising number said there were still supervised direct clinical opportunities for their students.” What’s more, APRN programs typically have additional clinical hours built into their curricula, so most spring graduates had already met or exceeded their requirements before the pandemic arrived.

Research Needed to Inform the Path Forward

Whether nursing programs should increase their use of simulation once the pandemic ends is open for debate. Some studies suggest that greater use of simulation would enhance learning because clinical experiences are often unpredictable, vary widely, and involve significant amounts of downtime. Recently, a small observational study attracted attention with its finding that in-person simulation is far more efficient than traditional clinical education—so much so, the researchers argue, that allowing one hour of simulation to substitute for two hours of direct clinical experience might actually enhance student learning.

Donna Meyer, MSN, RN, FAAN

“The benefits of simulation for prelicensure students have been demonstrated through evidence-based research,” says Donna Meyer, MSN, RN, FAAN, chief executive officer of the Organization for Associate Degree Nursing (OADN). “It is important for state regulatory bodies to review and consider the NCSBN National Simulation Study and other research when they set limits on how much high-quality simulation can substitute for traditional clinical hours.”

No one would argue with that sentiment, but there are gaps in the research record. The NCSBN study looked only at entry-level nursing students, which is why the organizations that oversee NP education and practice decided to stick with the status quo.

“Everyone agrees that simulation is important to augmenting clinical learning, but we lack evidence that simulation can replace direct patient care experiences at the graduate level,” says Mary Beth Bigley, DrPH, APRN, FAAN, chief executive officer of the National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties. “Fifteen national organizations came together and agreed that NP education requires a minimum of 500 direct care clinical hours and that all students must continue to meet competencies prior to graduation.”

Research is also needed into whether direct care experiences can be replaced with virtual simulation—those online clinical experiences that are easiest to implement given the constraints imposed by COVID-19. The question is whether virtual simulations are as effective as in-person simulations. These are typically highly structured and supervised by faculty who brief students before and after to help them prepare and process their learning.

Susan Forneris, PhD, RN, FAAN

According to Susan Forneris, PhD, RN, FAAN, director of the National League for Nursing (NLN) Center for Innovation in Education Excellence, there are efforts underway to find out. “Academic leaders in simulation are really trying to compile the evidence to better inform boards of nursing, who then can promulgate rules and perhaps allow for a different ratio of simulation to clinical hours,” she says.

Deborah Trautman, PhD, RN, FAAN

Information on changes in the use of simulation should also be forthcoming from the American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN), which sees simulation as a valuable tool to augment learning and advance nursing competency. “As faculty become more comfortable with this teaching platform, I expect to see the use of simulation expand across all types of nursing programs at a more rapid rate,” says Deborah Trautman, PhD, RN, FAAN, AACN president and chief executive officer. AACN plans to monitor the use of simulation, including faculty perceptions, in future surveys.

Nancy Spector, PhD, RN, FAAN,

At NCSBN, Nancy Spector, PhD, RN, FAAN, director of regulatory innovations, is currently in the process of reviewing the literature to get a better handle on the efficacy of virtual simulation. “The evidence is very strong for quality clinical experiences,” she says, “and there’s no evidence for allowing more than 50 percent simulation to count toward clinical requirements. I’m afraid that the current laxity will continue after the pandemic has passed. Boards that are already at 50 percent are now allowing up to 100 percent simulation, and in states where COVID-19 prevents people from getting together, they are moving to virtual simulation,” she says.

Bryan Hoffman

Whatever policymakers decide, there seems to be consensus about one thing. As OADN Deputy Director Bryan Hoffman put it, “Everybody should be relying on the same research to make decisions about these issues.”

Opportunities Ahead

As schools consider their fall semester options, Susan Forneris says the conversation has shifted to the logistics of potentially bringing students back to campus and into simulation labs. “They have to be able to maintain social distancing, wear face masks, have disinfection and temperature protocols, and then have a system that says students are cleared to be in the environment—everything down to what will happen if they go to lunch or use the restroom and then come back to the lab setting.” These procedures may constitute an additional simulation of their own, mirroring what students may eventually encounter at clinical sites.

Beverly Malone, PhD, RN, FAAN

Importantly, no one is arguing for the elimination of a mainstay of nursing education: encounters with actual patients. “The connection between the nurse and the patient in face-to-face clinical care is incredibly powerful,” says NLN’s chief executive officer Beverly Malone, PhD, RN, FAAN. “You can’t replace that patient who surprises you, who somehow connects with something inside you and makes you want to give more and help in a meaningful way.”

Ensuring that such opportunities remain available, regardless of external events, is part of the thinking behind the proposed practice/academic partnerships. In a recent editorial, Maryann Alexander, PhD, RN, FAAN, chief officer for nursing regulation at NCSBN, suggests the partnerships would allow clinical sites to integrate students and faculty into their workforce instead of shutting their doors to students during an emergency.

“Practice and education could partner and adopt this model as part of a healthcare facility’s and an education program’s emergency preparedness plan,” she wrote. “Concurrently, nursing education programs could be equipped with simulation scenarios to prepare students to work in a crisis.” In fact, schools with existing partnerships in Idaho, Iowa and Oregon have managed to keep students on-site, and clinical sites have benefitted as schools have shared scarce resources such as personal protective equipment.

Mary Beth Bigley, DrPH, APRN, FAAN

“What COVID-19 has done, for better or for worse, is made us move out of our comfort zones,” says Mary Beth Bigley. “We were ready for this transformation, and this has forced us, and I think the outcomes are going to be very positive.”