May 13, 2019

Red Tape Delays Nurse Practitioner-Ordered Home Care

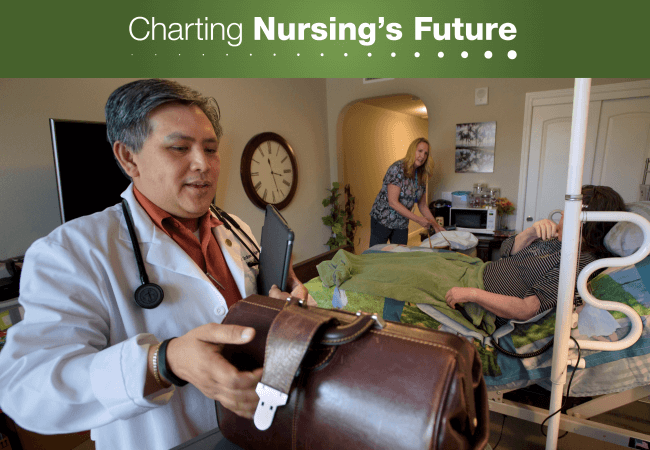

Home health care services ordered by nurse practitioners like Ron Ordona are sometimes delayed, putting patients at risk. Photo: Randall Benton

Could an outdated Medicare regulation be creating care delays that put patients at risk?

Ron Ordona, DNP, FNP-BC, provides primary and urgent care to older adult patients, most of whom are too sick to leave their homes for routine medical care. Many of Ordona’s patients rely on home care provided by a registered nurse (RN) who can monitor their conditions and perform critical tasks such as dressing wounds or making sure they take their medications. Medicare covers this service, but only if a physician signs off on it.

As a nurse practitioner (NP), Ordona is one of many primary care providers whose patients bear the brunt of this rule that can delay care. A fax requesting certification for home care may sit unseen on the desk of a busy physician alongside dozens of other requests for hours or even days—delaying the start of care while a patient’s condition deteriorates.

Last December, Ordona ordered a hospice evaluation for a patient with dementia who was moving toward the end of life. While the home health agency that would perform the evaluation and dispatch a hospice nurse waited for Ordona’s collaborating physician to sign off on the order, the patient declined to the point where she needed emergency care.

“You can only imagine,” says Ordona, expressing frustration at his patient’s ordeal, “someone with dementia, already feeling confused and combative, and in the ER—she didn’t need that.”

Nurse practitioner Ron Ordona provides primary and urgent care for home-bound patients. His orders for home health care require a physician’s certification. Photo: Randall Benton

Requiring a physician’s certification can delay communication in the other direction too. If a nurse providing home care identifies an immediate need for Ordona to see a patient, the home health agency will sometimes erroneously contact the signing physician instead. Ordona recalls one incident where this kind of delay resulted in a hospitalization. “By the time I got the call,” Ordona says, “bacteria from a urinary tract infection had spread throughout the body and [the patient] needed treatment with IV antibiotics.”

These kinds of delays do not appear to be isolated. Sue Mullaney, DNP, APRN, GNP-BC, heads up a task force that recently surveyed members of the Gerontological Advanced Practice Nurses Association (GAPNA) about their experiences referring patients for home care. Two-thirds of the 260 respondents who said they order home care reported difficulty getting the initial certifying signature and say their patients are “likely” to experience delays in care as a result.

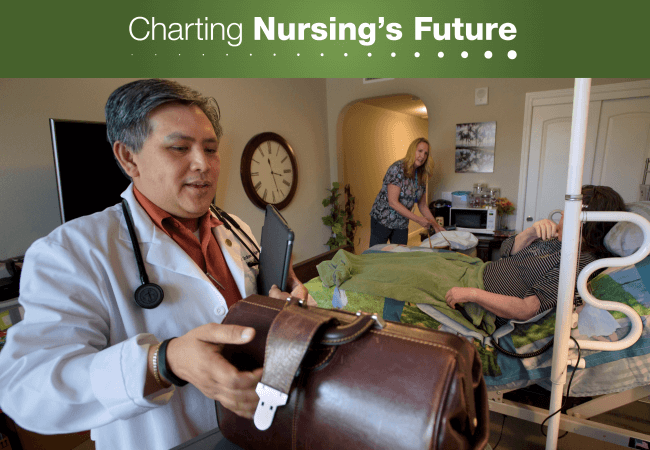

Although small in scope, “the survey objectively identifies that there are delays in care, and that’s an access issue,” Mullaney says. The survey did not determine how widespread the problem is, but an analysis by Avalere Health indicates that more than 3.4 million Medicare beneficiaries received home health services in 2017. With NPs making up the fastest growing segment of the primary care workforce according to an American Enterprise Institute report, there is reason for concern that the rule may continue to create delays for substantial numbers of patients.

There are proposals to remedy the situation. The Home Health Care Planning Improvement Act of 2019, first introduced more than a decade ago would allow NPs, clinical nurse specialists, certified nurse midwives, and physician assistants to certify Medicare patients for home health services. Despite being reintroduced several times over the years, the proposal has languished in Congress, where it awaits a cost estimate from the Congressional Budget Office. The Future of Nursing: Campaign for Action, an initiative of AARP Foundation, AARP and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, as well as AARP, have worked in support of this policy approach.

Another possible solution? The Department of Health and Human Services could change the regulation without legislation. As part of its “Patients Over Paperwork” initiative, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued a proposed rule to reform Medicare regulations that are unnecessarily burdensome for health care providers and suppliers. The proposal asked for comment on ways to reduce regulatory burdens, and GAPNA and the American Association of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) responded along with other health-professions organizations. In a recent letter, the groups asked CMS to use its regulatory authority to reduce the red tape causing home health care delays by expanding the definition of “physician” in the law or issuing a moratorium on enforcing the physician-signature provision.

Crucial home care services provided by registered nurses help keep patients out of the emergency room. Photo: Randall Benton

“We haven’t seen tremendous movement,” says MaryAnne Sapio, AANP’s vice president of federal government affairs, “but we know based on follow-up meetings that they are receiving the comments, and we feel we are being listened to.”

Meanwhile, Ordona draws inspiration from the older adults he serves. As a home care RN early in his career, his frustration at not being able to promptly address many of his patients’ needs inspired him to become an NP. “We are here,” he says of his community of NPs who are striving to provide the best possible care to their home-bound patients. He hopes government action will make that easier in the near future.